- Home

- Paul Twivy

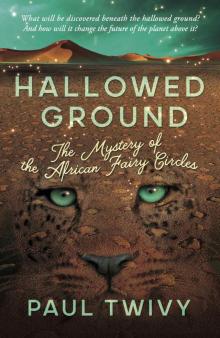

Hallowed Ground

Hallowed Ground Read online

Hallowed Ground

the mystery of the African Fairy Circles

Paul Twivy

Hallowed Ground

Published by The Conrad Press in the United Kingdom 2019

Tel: +44(0)1227 472 874 www.theconradpress.com [email protected]

ISBN 978-1-913227-37-1

Copyright © Paul Twivy, 2019

The moral right of Paul Twivy to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

Typesetting and Cover Design by: Charlotte Mouncey, www.bookstyle.co.uk

The Conrad Press logo was designed by Maria Priestley.

Quotes about “Hallowed Ground”

“Paul Twivy has taken the extraordinary, real-life phenomenon of Namibia’s Fairy Circles and turned it into a compelling story about the passion of the young to save the planet. This is a mystery thriller for the Extinction Rebellion generation.”

Vanessa Feltz, Broadcaster and Journalist

“The four most important words in the English language are... ‘Once Upon a Time’. We are a species bound together by stories and it is they that let our imagination take flight. Sometimes these stories are called myths and a huge idea springs into your mind...what if these aren’t stories? And you feel the hair stand up on the back of your neck.

This is one such story that will haunt your waking and dreaming hours with a question...What if? A great tale well told.”

Sir Tim Smit, CBE, co-founder of The Eden Project

“This timely and entertaining book not only captures the beauty and mystery of Namibia’s contrasting landscapes but also asks important questions about our relationship with the world around us and the future of our planet.”

The Right Honourable Linda Scott, High Commissioner of Namibia to the United Kingdom and Ireland

“A dazzling tale…. I can’t wait for the sequel.”

Rebecca Nicolson, journalist and publisher Inspired by the people, stories and landscapes of Namibia

for Gaby, my life companion,

and my children Sam, Josh, Max, Eve and Clara

Prologue

Ray County, Missouri, The United States of America

13th November 1833

The rain of the preceding days had cleared, giving way to a beautifully clear air that you could drink like water. It had been hours since the three-day-old moon had sunk below the horizon.

Alice woke up from the brightness inside the tent and called out in alarm.

‘Father, don’t keep stirring the fire. You’ll set the tent on fire!’

‘I haven’t touched the fire,’ he replied. ‘The embers are dying. You need to come out here. You’ll never see the like of this again.’

At the sound of his voice, high-pitched and trembling, stretched between excitement and fear, the whole family woke and left the tent.

Beth Wall exclaimed on behalf of her young family who were struck dumb.

‘My God, the whole heavens are on fire. Is it the end of the world, Edward?’ she asked as Alice and her brothers clung to her nightshirt from fear, sucking in the warm scent of her body for comfort.

It should have been the darkest hours before dawn, but the whole sky was ablaze with meteors. They were falling like a rain of fire, twenty or thirty of them ablaze every second. The tracks of light remained visible for several seconds. It was if their eyes were a camera set to a very slow shutter speed. The falling stars seemed to radiate from the North-east, but the sheer number of them confused every sense. The brighter ones left a trail of sparks like sky- rockets.

‘Fireworks!’ the youngest one cried.

Around the family, camped on the banks of the Missouri river, arose several hundred people as if a graveyard had just disgorged its dead. They were Mormon refugees sleeping out in the open. Many fell to their knees and started to pray.

Occasionally, a particularly bright fireball would explode as it neared the Earth, with a sound that echoed half-way round the planet.

‘It’s as if every star has cut free from its mooring,’ Edward cried.

The plantations were lit up for miles around. The white farmers could be seen calling all their slaves together, many of whom fell on their knees praying, arms held aloft, convinced it was Judgement Day. The owners ran around those whom they had enslaved, begging forgiveness and freeing them. Some were telling them, for the first time, who their mothers and fathers were, who they’d been sold to, and where they now lived. This brought brief tears of comfort to their black, upturned faces, followed by the agony that, now, they might never live to be reunited.

Everywhere, people were screaming and praying.

‘There can be no atheists on a night like this,’ Beth said. ‘Some of these stars as big as Venus!’

‘I’ve seen two as big as the moon,’ their eldest observed.

‘You see those that just skim the horizon?’ Beth asked Alice. ‘They call those “Earth-grazers”.’

Edward raked up the fire and found more logs. The family lay down next to it, holding each other tight. They watched until the rising sun eclipsed the fire-storm. From the southern states to Niagara Falls and the frozen wastes of Canada; from the land-locked plains of the mid-West to boats adrift on the icy Atlantic, people finally fell asleep at the touch of a new dawn on their skin.

Namibia, 1838, five years later

Captain Alexander dropped the flaming torch, sending light scurrying downwards and plunging the cave into darkness.

What he had seen remained imprinted on his retinas. It raced through his neurones like a train threatening to come off the tracks.

Was he hallucinating? Or had he really seen something that would change the way the human- race looked at itself?

He sank slowly to his knees and felt around the cave floor for the torch. Its coarse hessian tip was unmistakeable on his fingertips, as was the reek of kerosene as he raised it close to his face.

He struggled to remember where he’d put the matches. Then he remembered the feel of them at the bottom of his canvas bag.

His fingers trembled as he tried to strike one. The first match sent sparks shooting down his legs in a brief explosion. The cave lit up momentarily.

The second match was steadier, and he lifted the flame to his torch which hissed and spluttered back to life.

There they were: fifteen or more, almost organic in shape, laid out in niches along the cave.

Then his eyes rose upwards again. There were four paintings on the ceiling. He propped the torch up and tried to sketch them in a notebook, but his hands couldn’t stop shaking and he was forced to stop.

If only the Herero men hadn’t abandoned him, their superstitions blazing in their eyes, their priest unconscious on the floor. Then he would have had witnesses, help and comfort, and not been left feeling like a madman, utterly alone.

Mind you, they had been right to be afraid. The knowledge was too much to bear.

The Royal Geographical Society, which had funded his mission, would blacklist him. The Church and the Army would call him a traitor. He would be an outcast.

He left the tomb and brought back a platoon the next day to hide the entrance from the world. No-one was ready for this. Perhaps in a hundred or so years they might be…

1

Convergence

September 2019

South African Airlines flight SAA 349, from Cape Town to Windhoek, had suddenly dropped thousands of feet in a matter of seconds over Fish River Canyon.

Coffee, juice and even eg

g from the airline breakfasts had shot as high as the overhead lockers and was now dripping like a gelatinous rain on the passengers. White trays, plates and cups littered the gangways like moon rocks. Oxygen masks had dropped from the ceiling like yellow flowers on plastic tendrils.

Several passengers screamed. Cabin crew were thrown backwards and then tried to rescue some dignity.

Joe would have panicked more if he hadn’t been so exhausted. The overnight flight he and his parents had taken from New York to Cape Town had seemed never ending. They had passed through thunderstorms mid-Atlantic and he’d tried to work out if it was better or worse if a plane crashed into the sea rather than the land. Sea is a soft landing he’d reasoned, but then concluded it must be more dangerous to plunge beneath the waves. He’d managed to shut down his imagination before he drowned in it.

Joe Kaplan was fourteen years old and below the median height of his class, by a factor that he knew exactly. He’d put insoles in the heels of his shoes for a few weeks, until the pain in his calves got too much. He was thin and lithe and the best tactician on the football team, so was probably never in danger of being bullied for his height… it just felt like it. His face was beginning to grow a light down of hair which he examined obsessively in the mirror every morning. He longed for the full-on, hipster beards of his Silicon Valley heroes. Much to his mother’s annoyance, and partly because of it, he had grown a long fringe of hair. He often kept his face angled slightly down and to one side, so that the fringe flopped over his right eye. He liked seeing the world but the world only half-seeing him.

He knew the pattern of these long journeys only too well. It had become the rhythm of his life: his parents moved constantly because of their jobs. Joe felt like a citizen of everywhere and of nowhere.

He had followed his usual strategy and stocked up a horde of magazines and snacks as sandbags against boredom: Sudoku puzzles, two paperback editions of ‘Impossible Math Puzzles’ and bags of Haribo. At least he could take his mind for a run. The first in-flight movie had held him in a spell, the second merely tugged at his attention and the third had felt like a glut and he’d fallen asleep.

Cape Town airport had been a blur to him, drowning in an early morning stupor, but he was still aware of the blissful light pouring in from every direction. Africa was beginning to stir in him even then and soared as their plane headed south again over the sea-swollen Cape, and then turned sharply over Table Mountain, heading north towards Namibia.

‘Robben Island down there,’ his father, Ben, had said, ‘where Mandela was imprisoned.’

It seemed to Joe that the sea around the island glistened, as if responding to his father’s remark.

His father always wanted to share knowledge and Joe always felt a duty to show keen. Ben Kaplan was about to be fifty: a fact he tried to hide. He disliked airline safety belts as they reminded him that he was developing a paunch. He was an anthropologist at Columbia University in New York, distinguished but not as distinguished as he’d once hoped. Joe envied his father’s beard although Ben had, in truth, grown it to offset his baldness. Joe’s mother had once told her husband that his forehead reminded her of a Roman Emperor. Ben had carried this remark proudly in his head ever since as a consolation for having lost his hair.

They’d hit turbulence over a landscape that could stupefy even when it was calm. Fish River Canyon had a deeply cutting river which flowed round and back on itself like a ribbon, creating a Manhattan-like island of solid rock in its middle. Its scale became terrifying as they seemingly dropped into it.

A second jolt, worse than the first, hit the plane like a shockwave.

Other passengers threw their panic-stricken gaze out of the windows and prayed for a steady horizon.

This time it hit Joe with full force. His mind sharpened from stupor to alert. His hand grabbed the seat in front, his knuckles turning white.

‘I think it’s just bad turbulence,’ his mum said, trying to reassure herself as much as him. She wanted to hold his hand, but she knew he would reject it.

Barbara Kaplan was only two years younger than her husband, but it looked like ten, as she frequently reminded him. She prided herself on being slim for her age. Although she had to power-dress for her job, her hair was a rebellion: long, dark-brown and straggly. Her face when it wasn’t taut with stress, was all kindness. Her features were strong but balanced. She was shorter than most American women, a trait she worried her son had inherited.

Joe had always been tight inside, even as a toddler. He’d sailed through his bar mitzvah, thank God, because he was bright and conscientious. Yet, Barbara worried that his intensity and awkwardness cut him off from other people. She looked down at Namibia hoping that somewhere here he would find the good friends he deserved and needed.

‘Don’t worry. These planes can resist massive shocks,’ his father soothed. ‘We haven’t dropped nearly as far as it feels.’

A reassuringly professional voice threaded its way through the cabin and into Joe’s head.

‘Ladies and Gentlemen, this is the Captain. Please don’t be alarmed. We hit an air pocket as we crossed into Namibia, but the turbulence should soon clear. Crew, please be seated for now.’

A few minutes later the plane steadied itself, although small ripples of turbulence still licked its belly. The screams had gone, now slightly ashamed of their own absurdity.

Slowly spines unfurled, fingers loosened, minds cleared, panic dispersed, lips lost their frantic prayers.

Joe’s recurring thought that he might ‘die in Africa before living in Africa’ ebbed to the back of his mind and his breathing slowed. At the corner of his vision, through two port-hole windows, appeared a pattern. It was a tessellation in the sand, a blistering of the landscape like a pocked face. It stretched for mile after mile: circles of different sizes in rows and columns that didn’t behave. To Joe it looked like Nature playing havoc with maths.

‘Fairy circles,’ he heard his father mutter.

Freddie strained to see through the lingering fog. A chill had suddenly come over him, brought on by the desolate coastline that now lay ahead.

Freddie Wilde had only just turned fourteen, but this was already the third country he was going to call home. Or was it the fourth? He couldn’t remember. He was tall; almost as tall as his father, and his mother feared the ship’s railings were illegally low as he leaned over them, straining to see. Freddie’s blond hair had been blown into even more of an extravagance than normal by the morning breeze. His face was unmistakeably English, chiselled with deep-set, brown eyes that seemed to treat everyone as the only person alive when he gazed at them. His wide mouth had, until recently, always stayed slightly open, as if he couldn’t breathe through his nose. Now it was often shut, to hide the train-tracks that imprisoned his teeth.

‘Why have we come to live here, Dad?’ Clara, his nine-year-old sister asked, adding, ‘I thought Africa was hot!’

Clara Wilde’s upturned face never lost its look of curiosity. She drank in every detail of the world. Her blonde, curly hair tumbled half- way down her back and was constant work for her mother to control, if also a source of joy. She had ‘puppy fat’ cheeks that everyone adored but she hated. Clara’s eyes were as big as her appetite, but her mouth was tiny. It was always a shock for people to hear such a powerful voice come from such a modest source.

‘It is, darling,’ her father Ralph reassured, putting his arms round her in an envelope of warmth. ‘Most of the country is beautifully hot. Three hundred days of sunshine a year, they say. But this is the Skeleton Coast.’

‘Skeletons?’ Clara cried in horror.

‘Of ships,’ Ralph added to reassure her.

Even at this ungodly hour of the morning, Ralph Wilde looked ‘dapper’ in his early fifties, to use one of his favourite words. Ever since he was a child, he’d been neat, everything trimmed and in place. Had he not been so charming,

this neatness might have alienated his ‘scruff-ball’ schoolfriends. Freddie had inherited his thick hair from his father, although Ralph’s had been a sandy brown since his late teens. He had the smooth and confident looks of a diplomat.

‘So, what causes the fog?’ Freddie asked, lost in an atmosphere of Victorian London he’d not anticipated. The fog seemed to slide its fingers into his hair, causing a shiver to pass through him.

‘It’s a meeting of opposites- the cold ocean and the hot land,’ one of the officers explained from behind where they stood. Their cruise ship was sailing at a speed gravely respectful of the coast’s fearsome record of ‘ship-wrecking’.

‘And the shipwrecks?’ Freddie asked.

‘Over a thousand of them, would you believe,’ the officer replied. ‘That ship in front of you is one of the most famous.’

Freddie put the binoculars to his face again.

‘I can see it now,’ he cried.

‘Let me see,’ cried Clara, trying to wrest the binoculars from her brother’s grasp.

‘Get off, Clara. I’ll give it to you in a minute,’ Freddie snapped.

The ship looked unreal. A forlorn creature, lop-sided and skeletal, drained of life and purpose. Its guts spilled out sand and rust. It had broken in two, like a miniature Titanic on the seabed. It was difficult to judge its scale because of the vastness of the coast that had lured and snapped it like a toy.

When his father had been given his new posting as British High Commissioner to Namibia, it was Freddie’s mother who had suggested arriving by ship. Freddie had overheard her saying, ‘Freddie and Clara will love it….so much more memorable than just flying into Windhoek.’

She hadn’t anticipated quite how chilling it would be. But then nothing phased Anne Wilde for long. She was five foot ten inches tall and had excelled at netball at school, as well as being academic. Becoming Head Girl had been inevitable. Her smile was broad and welcoming, and her shoulder-length hair had a girlish vitality that disguised the fact she was forty-four.

Hallowed Ground

Hallowed Ground